POWER OF PORTRAITS

OPEN THINKING ON THE FUNCTION AND POWER OF PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY

by Ashley Mercado

Artes Magazine, 2008

The Un-choreography of One Light

It is said that two people exist in every portrait, the subject and the photographer. Portrait photography has been noted and even celebrated for this tension. But the duality can serve to undermine the singular intent specific to portraiture: the depiction of an individual.

Swiss/American portrait photographer Rebecca Zilenziger has worked out of her studio and darkroom in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico for sixteen years. Through travel and studio work, her photographic projects range from natural disasters and mental disorders, to construction sites and obscure or well-known cultural figures. By refusing to place herself at the center of her work, Zilenziger has amassed a body of images that reevaluate cultural perception, with the intent of making people see things in ways they haven’t before.

For the series of images on children with autism, the use of one light became a fulcrum for interaction in the studio. In this series, shot in Providence, Rhode Island, Zilenziger worked at a behavioral center that associates child management to developmental research. The project demanded a proposal, a slew of releases, support from clinical staff, and several trips to the area.

The notion of disconnection constrains professional and parental advocacy for children with autism. But when the children entered the room, the one light became a point for their attention. Each image in the series depicts very real and very direct moments of eye contact. Research to this day strives forward to contextualize autism within the diversity of functioning human behaviors. Zilenziger represented children with autism in a visual accuracy, free of the glut of processed information that manipulates facts and subtleties to its own accord.

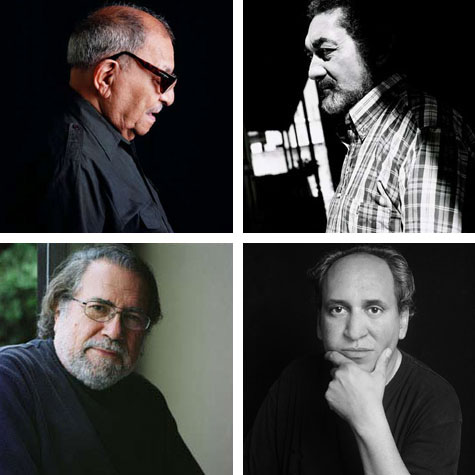

Zilenziger’s images of significant and historic Puerto Rican artists came from a simple search for a concise book on the subject, “to see their faces,” she said. By and by, Zilenziger found that no such book exists. She consequently sought out and photographed Puerto Rican artists by going to their homes and studios, or inviting them to hers. Each artist in the series is significant, their work is on display at museums, they have earned gallery representation, and are widely collected. A concern over the inability to identify the faces of Puerto Rican artists is evident in the series itself. Each artist takes up the photograph in its entirety. The area surrounding the artist is out of focus, obscured, and made unimportant. In an effort to connect the viewer to the individual, nothing else distracts the introduction – an introduction Zilenziger makes immediate.

This series of Puerto Rican artists is emblematic of a larger issue that the art world and the public contend with: if the name, the work and the face of the artist are not in concert with one another, then the artist and their work is marginalized. As with most Latin American art and culture, the borders of recognition have been heavily policed.

Photographers lovingly use three, four, even five lights or more. And though their work might be incredibly eye catching, there is a glitz that verges on the grotesque with its curtsy to advertising. Zilenziger is not subtle about her dislike of over-illumination, and she uses either natural sunlight or a monolight Swiss-made Elinchrom, and never at the same time. Her one light serves as a focus point – without any visual roadblocks that clutter or congest viewer access or over produce the image with artificiality. Zilenziger presents individuals emerging from their own natural shadows.

Children with autism suffer assumptions about their behavior just as formidable Latin American or Hispanic artists continue to sustain obscurity. In both instances, there is an unacknowledged truth. In each photograph, the individual looks out from behind the eyes of their own life experience, or places their body in the comfort of their own disposition. Zilenziger’s photographs show the “disorder” as a social perception rather than the condition of autism or the circumstance of obscurity. The images are not tainted by an opinion, but depicted in a single moment of particular reality.

Countless portrait photographers insert themselves into the images they produce. Annie Leibovitz favors the choreography of public celebrity over the private persona of her subjects. Diane Arbus attacked the concept of “proper” art through her work. Richard Avedon’s portraits were said to be first and last, Avedon’s. And while these intimate motives and meanings are vital to the evolution of photographic portrait art, the mimetic repetition of technique has reduced portraiture to the personality of the photographer.

Today, the rogue portrait photographer is one who refuses to place themselves anywhere except behind the camera. Rather than congest the image with ulterior motives, they allow the photograph to focus in on its subject. As a portrait functions to honor and remember, Zilenziger remembers to honor the function of the portrait.